PRE-RIVALRY

They’ve been playing prep-level football in Flagstaff for well over a century. While the central point of Flagcoco is to celebrate the modern rivalry between Flag High and Coconino, a little set-up might be beneficial for the historically inclined. Flagstaff has always loved its football, from the youth leagues to the Arizona Cardinals holding their summer practices at NAU, and it started long before 1969.

The Early Years

Going as far back as 1900, exhibition games have been played in Flagstaff. Northern Arizona Normal School (known today as Northern Arizona University) played their first organized schedule in 1915, but prior to that, a school team would play on occasion; for instance, on Thanksgiving Day 1912 the Normal team played the Forest Service College Men. They also played regional teams, mostly high schools (the only established football presences in the area). 1915, though, was the year they put their first recognized schedule together. It included two games against Winslow, two against Prescott, one versus Phoenix High, and one against Tempe Normal School (Arizona State University). This was a time when the railroad was the primary form of travel between cities, and the schedule revolved around the restraints and cost of this reality. For instance, Normal would travel to Winslow, play, both teams would travel back to Flagstaff on the same train and play a day or two later. When Normal would travel to Phoenix, they’d play both the high school and Tempe Normal on the same trip, a day or two apart, before returning home. That first year was rough for Normal, playing more established teams; they finished with a 2-4, beating Winslow twice, struggling in both games against Prescott, and getting thrashed by Phoenix and Tempe Normal (losing the latter by a score of 72-3).

Going as far back as 1900, exhibition games have been played in Flagstaff. Northern Arizona Normal School (known today as Northern Arizona University) played their first organized schedule in 1915, but prior to that, a school team would play on occasion; for instance, on Thanksgiving Day 1912 the Normal team played the Forest Service College Men. They also played regional teams, mostly high schools (the only established football presences in the area). 1915, though, was the year they put their first recognized schedule together. It included two games against Winslow, two against Prescott, one versus Phoenix High, and one against Tempe Normal School (Arizona State University). This was a time when the railroad was the primary form of travel between cities, and the schedule revolved around the restraints and cost of this reality. For instance, Normal would travel to Winslow, play, both teams would travel back to Flagstaff on the same train and play a day or two later. When Normal would travel to Phoenix, they’d play both the high school and Tempe Normal on the same trip, a day or two apart, before returning home. That first year was rough for Normal, playing more established teams; they finished with a 2-4, beating Winslow twice, struggling in both games against Prescott, and getting thrashed by Phoenix and Tempe Normal (losing the latter by a score of 72-3).

The next few seasons showed general improvement in the Normal team. The awe of an incredible 108-0 loss to Albuquerque notwithstanding, they went 5-1 in 1916. Travel  considerations, the influenza pandemic, and world war meant reductions in scheduling; they only played five games total in the three seasons from 1917 to 1919, four of them against Winslow.

considerations, the influenza pandemic, and world war meant reductions in scheduling; they only played five games total in the three seasons from 1917 to 1919, four of them against Winslow.

Meanwhile, Emerson High School had been playing intermittently. Founded in 1895, it was the first high school in Flagstaff, and though Emerson and Normal played the same teams on a generally regular basis, the two did not square off against each other until 1920. That year, they played each other twice; in a preseason scrimmage they played to a 6-6 tie, then later Normal crushed Emerson in midseason, 32-6. That game should be considered the first intra-city game played in Flagstaff

The First City Championship Game

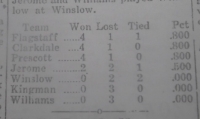

When Flagstaff High School opened in 1923, it took over for Emerson, which was demoted (it continued on as a grade school until 1975). Its football team assumed a place in a loosely-constructed Northern Arizona Conference that, over the next two decades, included the high schools from Clarkdale, Holbrook, Jerome, Kingman, Prescott, Snowflake, St. Johns, Williams, and Winslow. The Normal School was in this mix as well at first, continuing to play the regional teams as well as making trips to the Phoenix area and elsewhere; by now they had taken the moniker “Lumberjacks”.

Coached by R.G. Stevenson, Normal was having one of its better seasons in ‘23, shutting out four of their first five opponents, including a victory over the always-tough Jerome Muckers, 18-0. Flag High’s inaugural season wasn’t too bad, either; led by Head Coach H.W. Denham, their very first varsity game was against the well-established Winslow team, and they fought to a 6-6 tie. After beating Jerome and losing to Clarkdale, they beat Winslow in a rematch, 12-0, and went into their finale with a 2-1-1 record.

That finale was against Normal, and the Flagstaff media recognized they had the potential for something special: a crosstown matchup between two solid teams. Slated for November 23, the game was scheduled as part of an all-day ceremony to celebrate the dedication of McMullen Field, Normal’s home gridiron. The headline in the Coconino Sun on that day read NEW M’MULLEN FIELD WILL BE DEDICATED TODAY AND THE FOOTBALL SUPREMACY PROBLEM WILL BE SOLVED.

A crowd of a thousand people (Flagstaff’s population hovered around 4,000 at the time) gathered to watch the city’s two teams slug it out. Flag High won the coin toss and elected to defer. They kicked off, and Normal ran it right down their throats. Multiple runners ran left, right, and up the middle, gobbling up yardage, with the Green and Brown unable to stop them. Charles Fillerup ended the drive with a three-yard blast for a touchdown, and after the extra point, Normal was up 7-0 just four minutes in. Flag High was game, but ineffective on offense. Near the end of the first half, Normal quarterback Lynn Camp scampered through the Flag High defense for fifteen yards and another score. The halftime score was 14-0. It stayed that way until the fourth quarter, and that’s when Flag High made their run. Having driven to the Normal 1 by the end

A crowd of a thousand people (Flagstaff’s population hovered around 4,000 at the time) gathered to watch the city’s two teams slug it out. Flag High won the coin toss and elected to defer. They kicked off, and Normal ran it right down their throats. Multiple runners ran left, right, and up the middle, gobbling up yardage, with the Green and Brown unable to stop them. Charles Fillerup ended the drive with a three-yard blast for a touchdown, and after the extra point, Normal was up 7-0 just four minutes in. Flag High was game, but ineffective on offense. Near the end of the first half, Normal quarterback Lynn Camp scampered through the Flag High defense for fifteen yards and another score. The halftime score was 14-0. It stayed that way until the fourth quarter, and that’s when Flag High made their run. Having driven to the Normal 1 by the end of the third, Vic McClure ran up the gut to get the high schoolers on the board. The drop kick conversion failed, but the deficit was narrowed to 14-6. The ensuing kickoff was a squib kick, and Flag High recovered at midfield with growing momentum, but they couldn’t convert. They mustered one last drive, and hard running coupled with sloppy Normal tackling put Flag High in scoring range in the final minutes. McClure pounded it across the goal line from two yards out with just nineteen seconds left, but the kick conversion was blocked, and the Flag High rally came to an end.

of the third, Vic McClure ran up the gut to get the high schoolers on the board. The drop kick conversion failed, but the deficit was narrowed to 14-6. The ensuing kickoff was a squib kick, and Flag High recovered at midfield with growing momentum, but they couldn’t convert. They mustered one last drive, and hard running coupled with sloppy Normal tackling put Flag High in scoring range in the final minutes. McClure pounded it across the goal line from two yards out with just nineteen seconds left, but the kick conversion was blocked, and the Flag High rally came to an end.

Normal 14, Flagstaff 12

The same sort of excitement hit again in 1924 when the two teams met, this time on Armistice Day (football was part of Flagstaff’s traditional holiday celebration). Under W.E. Rogers’ tutelage, Normal was on fire, going into the rivalry game with a perfect 4-0 mark, winning by a combined score of 185-6. Denman and Flag High had a solid 3-2 record, shutting out Williams and Winslow, beating Prescott, but losing to Clarkdale and Jerome. Normal was overwhelmingly favored; they had beaten Jerome 64-0, and Jerome in turn had beaten Flag High 26-6. Today’s game was to be played at the high school’s home field at City Park, but Normal’s size and larger talent pool outweighed any home field advantage.

Flag High received to start the game, and they played a much more wide-open game than they had the previous year. They mixed the run and the pass better and were able to move the ball more effectively. A goal line stand in the second quarter gave the high schoolers the ball on their own 2, to which they were able to run on the Lumberjacks in large chunks. Between Clifton Williams, Walter Runke, and Edward Conrad, they ran roughshod through the Normal defense, with Williams scoring from ten yards out. The conversion was missed, and the half ended with Flag High up 6-0. The second half started with a bang, as Normal’s Lynn Camp took the kickoff and raced 85 yards for a score; a successful drop kick put the Jacks up 7-6. The high schoolers hung tough, did not let Normal build on that lead, and in the fourth quarter, they put together another drive that ended with another Williams touchdown; with the drop kick good, Flag High was leading the collegians 13-7. They halted Normal’s next drive at their own 25, and from there they continued to pound at the Normal defense, eating yardage and the clock, even threatening to score again as they made it as far as the Normal 12 when the final whistle blew.

Flagstaff 13, Normal 7

Despite the popularity of two intense games between successful programs, this would be the last time Flagstaff High and Northern Arizona Normal School would meet. The loss sent Normal into a tailspin, losing the rest of their games and ending ’24 at 4-4. Flag High’s season ended with four wins and two losses. Starting in 1925, Normal, now known as Flagstaff Teachers College, sought to step up their level of competition and play more collegiate foes, and the money exchanging hands on this level was much more lucrative than playing regional high school teams for just the sake of playing. In ’25, the Lumberjacks only had three high school opponents (Jerome, Clarkdale, and Prescott) and dominated them all; in ’27 and ’28 they just had Phoenix Indian School, and by 1929 the transition was complete, as their schedule was all collegiate. The 1924 “city championship game” was the last Flagstaff would see for 45 years.

The Championships of the 1930’s

The Championships of the 1930’s

H.W. Preston took over for Denman in 1925, and by the end of his four-year tenure, he had won a share of the Northern Arizona championship. This was the start of a mini-dynasty for Flag High (in ‘25 they donned the name “Eagles”); between 1928 and 1937, they won the championship, shared or unshared, five times.

It must be understood that, before 1959, there was no such thing as an official state champion in any of Arizona’s football classes. Neither the Arizona Interscholastic Association nor the Arizona Republic recognize any claims to titles before that. When Flag High talks about the championships they won or shared in this era, they refer to the Northern Arizona Conference. There was no apparatus in place for recognition of a statewide champion, no playoff system, no polls. Northern and southern Arizona were separate entities where prep football was concerned. Flag High had never even played a game south of Prescott.

Rollin Wheeler took over as the Eagles coach in 1929, and by 1931, they had their second championship, their first outright. They did it again in ’34 and ’35 under the field management of their first true superstar, Eddie Jakle; in the title-clinching game at Jerome in ’35, Jakle’s touchdown pass to David Turner proved to be the only score in the Eagles’ 7-0 victory. These two conference titles were considered state titles, even by the newspaper writers in Phoenix who believed the Eagles could defeat the powerhouse teams there and in Mesa. They even tried to talk up the idea of an extra game, a playoff, especially in ’35 between the Northern and Southern representatives to determine a true state champion.

Rollin Wheeler took over as the Eagles coach in 1929, and by 1931, they had their second championship, their first outright. They did it again in ’34 and ’35 under the field management of their first true superstar, Eddie Jakle; in the title-clinching game at Jerome in ’35, Jakle’s touchdown pass to David Turner proved to be the only score in the Eagles’ 7-0 victory. These two conference titles were considered state titles, even by the newspaper writers in Phoenix who believed the Eagles could defeat the powerhouse teams there and in Mesa. They even tried to talk up the idea of an extra game, a playoff, especially in ’35 between the Northern and Southern representatives to determine a true state champion.

Such a game never happened, mostly because the powers that be at Flag High wouldn’t allow it. Simply put, there was no system in place for a playoff, so throwing this sort of game together at the last minute was not something Wheeler and J.P. McVey, Flag High’s principal, wanted to encourage. What discussions were made, they were one-sided, with the Phoenix contingency trying to dictate terms to Flagstaff (a theme that continues to rankle all of Arizona outside the Phoenix metro area); such a game had to be played in Phoenix, and Flag High would have had to pay all their own expenses. The game would have been played in early December, cutting into preseason basketball practice and study time. Ultimately, the game of football, while popular in Flagstaff, was not so important as to toss out the rest of the winter school calendar, nor was it important enough for McVey and Wheeler to let themselves be talked down to by the bigshots in Phoenix. They were satisfied with being Northern Arizona champions, and that was the end of it.

Could the Eagles have beaten Phoenix or Mesa? From 1929 to 1935, they won 33 games while losing just four and tying four. In their back-to-back championship years, they were not only undefeated in thirteen games, but won eleven of them by shutout, they didn’t give up a single point in ’34 and allow ed only thirteen points in ’35.

ed only thirteen points in ’35.

Wheeler and the Eagles won one more title in 1937 with a 4-1-2 record. After that and for the rest of Wheeler’s tenure, they struggled, winning just one game in each of the next three seasons. He stuck it out through 1942 and 1943, when transportation difficulties due to world war called for shortening the football season. Ultimately, the ’42 schedule was cut in half, the first half played in ’42, the second in ’43.

The 1940’s and 1950’s

Don Clark took the helm in 1944. By the time he left in ’54, the Eagles were no longer a regional team playing regional opponents. They became a statewide power.

They continued the same Northern Conference schedule until 1949, when, for the first time, they played teams from Phoenix and elsewhere. After losing a tight game to Coolidge 7-6, they beat up on Phoenix Indian School, 33-7. They ended the year with a loss to West Phoenix, 20-12, and finished with a 5-4 record that included a forfeit to Winslow, but the genie was out of the bottle, and the Eagles would never be a podunk team ever again.

podunk team ever again.

In ’51 and ’52, Clark and the Eagles again won the Northern title, but their schedule was not limited to just Northern Arizona opponents. They played teams from Needles and Blythe, California, as well as Boulder City, Nevada. After ’53, they would play out-of-state teams on occasion, playing a schedule that took them all over Arizona. They never completely abandoned their old schedule, but by being able to compete across the state, they were able to strike a balance between playing traditional rivals like Winslow and  Prescott as well as go to Phoenix and elsewhere and win.

Prescott as well as go to Phoenix and elsewhere and win.

The Legend of the Flagstaff Flyer

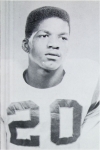

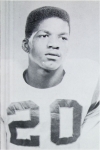

When a certain skinny freshman walked onto the Flag High field for summer practice in 1960, odds are neither Head Coach John Ply nor anyone else knew what they had on their hands. When he graduated in ’64, he was a chiseled hulk who had rewritten the record books, not just in football, but in baseball and basketball as well. James Dugan is not only the best athlete Flag High ever produced, or Flagstaff as a city for that matter, but he is among the greatest in the history of Arizona high school athletics, and you deserve to know why.

When a certain skinny freshman walked onto the Flag High field for summer practice in 1960, odds are neither Head Coach John Ply nor anyone else knew what they had on their hands. When he graduated in ’64, he was a chiseled hulk who had rewritten the record books, not just in football, but in baseball and basketball as well. James Dugan is not only the best athlete Flag High ever produced, or Flagstaff as a city for that matter, but he is among the greatest in the history of Arizona high school athletics, and you deserve to know why.

His place among the Eagles’ greats had already been secured by the time his senior year rolled around. He had already lettered nine times, having played three sports on the varsity level since he was a freshman. He was receiving All-State honors in all of them, even as a freshman outfielder. As a sophomore, he was scoring 23.2 points a game on the hardwood and set the school hoops record with 41 points against Coronado. His junior year, he won All-State recognition as a catcher on the diamond, a forward on the court, and a defensive back on the gridiron.

But his senior year of ’63-’64 was to be something that galvanized the city, not just for being a once-in-a-generation athlete, but for being a man of his times. Dugan roared through the football season, and nearly every game was the stuff of legend. He scored three touchdowns when the Eagles hosted Brophy at Lumberjack Stadium and twice on long runs against St. Mary’s. He broke records against North Phoenix, scoring five touchdowns and four conversions, giving him an incredible 34 points on the night, a school record that would last almost three decades. Add another four touchdowns the next week against Sunnyslope and four more in the finale versus Cortez. He finished ’63 with 1,106 rushing yards on 101 carries (for an astonishing average of almost 11 yards), 22 touchdowns, and 155 points. Not only did he receive All-State honors for his prowess running the ball in Jim Brown-like fashion, but was also named the Arizona Player of the Year.

At the end of his four years of football, he had rushed for 2,739 yards, gained another 1,065 receiving, and scored 315 points, all against defenses designed specifically to stop him. The Eagles lost only six games in his four years in pads.

For as great as his senior football season was, the basketball season started even better. If he was Jim Brown on the football field, he was Wilt Chamberlain on the hardwood, scoring points and grabbing rebounds like a man among boys. He scored 21 in the opener against Washington, 32 against St. Mary’s, but the next night, in Winslow against the Bulldogs and their own superstar, Isaac Bonds, was over the top. The Eagles set the team record with a 98-64 win, but it was the James Dugan Show as he hit 24 of his 38 shots, went 6-for-12 from the line, and scored a mesmerizing 54 points, shattering his own school record.

For as great as his senior football season was, the basketball season started even better. If he was Jim Brown on the football field, he was Wilt Chamberlain on the hardwood, scoring points and grabbing rebounds like a man among boys. He scored 21 in the opener against Washington, 32 against St. Mary’s, but the next night, in Winslow against the Bulldogs and their own superstar, Isaac Bonds, was over the top. The Eagles set the team record with a 98-64 win, but it was the James Dugan Show as he hit 24 of his 38 shots, went 6-for-12 from the line, and scored a mesmerizing 54 points, shattering his own school record.

Next up for Dugan and the Eagles was the infamous night in Prescott. No one doubts the facts of the matter; with five seconds left and Flag High clinging to a three point lead, Dugan was called for an offensive foul, his fifth. In disgust, he threw the ball at Badger Don Thayer and socked Randy Emmett in the face. The gym erupted in pandemonium and had to be cleared. The AIA, after a month-long investigation, suspended Dugan for the remainder of the basketball season. These facts are not in dispute.

What is in dispute, even fifty years after the matter, is why the incident and the subsequent suspension happened. If you talk to Prescott people, they will tell you it was a tough, hard-fought game, as it usually the case when the Eagles and Badgers play in any sport, and Dugan couldn’t handle it, so he punched out a benchwarmer. Flagstaff folks will tell you Dugan was hacked and called racial slurs all game, the referees did absolutely nothing about it, and while no one condones violence, one could hardly blame Dugan for lashing out. For his part, Dugan considered the episode a moment of weakness, and he has always been apologetic about the matter.

What is in dispute, even fifty years after the matter, is why the incident and the subsequent suspension happened. If you talk to Prescott people, they will tell you it was a tough, hard-fought game, as it usually the case when the Eagles and Badgers play in any sport, and Dugan couldn’t handle it, so he punched out a benchwarmer. Flagstaff folks will tell you Dugan was hacked and called racial slurs all game, the referees did absolutely nothing about it, and while no one condones violence, one could hardly blame Dugan for lashing out. For his part, Dugan considered the episode a moment of weakness, and he has always been apologetic about the matter.

An excellent article on the matter was written by Steve Stockmar in December 2013 in the Prescott Daily Courier, and it should be considered the final word on the matter.

Whatever frustration Dugan had for having his basketball season shortened to just ten games, he saved it for baseball when it came around. He had an astonishing .592 batting average in ’64 and a .497 average for his Flag High career, with 13 home runs and 60 RBI in 58 games.

Dugan received All-State recognition for all three sports his senior year. At one point or another, he also received All-American honors in all three sports as well. He had his pick of scholarship offers, originally committing to Arizona State, but (likely because of the incident in Prescott) ended up going to Ohio State to play for the great Woody Hayes. As a cocky freshman, Hayes asked him if he thought he was great; Dugan said yes. Hayes then took Dugan to a Louis Armstrong concert and met the great jazz musician backstage, after which he told the new collegian, “Don’t ever talk to me about imagined greatness. THIS is greatness.”

For as talented an all-around athlete Dugan was, he never made it at Ohio State. Some speculated it was because of poor grades, but Dugan maintained it was because of an injured ankle the Buckeye staff neglected to care for. He spent several years playing minor league baseball, including, among others, the A’s and Mets organizations. Though he never reached the sort of acclaim on the collegiate or professional levels that he did in high school, the Arizona Republic placed him #9 on their list of the greatest Arizona athletes of the 20th Century, and he is a charter member of the Arizona High School Hall of Fame. In August 2012, the Flagstaff Sports Foundation named him to their Hall of Fame as well.

For as talented an all-around athlete Dugan was, he never made it at Ohio State. Some speculated it was because of poor grades, but Dugan maintained it was because of an injured ankle the Buckeye staff neglected to care for. He spent several years playing minor league baseball, including, among others, the A’s and Mets organizations. Though he never reached the sort of acclaim on the collegiate or professional levels that he did in high school, the Arizona Republic placed him #9 on their list of the greatest Arizona athletes of the 20th Century, and he is a charter member of the Arizona High School Hall of Fame. In August 2012, the Flagstaff Sports Foundation named him to their Hall of Fame as well.

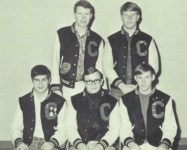

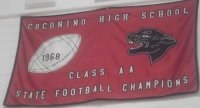

Coconino’s Miracle Season

Until 1967, Flag High exclusively enjoyed Flagstaff’s football talent pool. It was cut in half when Coconino opened. John Ply’s assistant, Bill Epperson, was the Panthers’ first head coach, and though they fielded only a semi-varsity team in Year One (several of their games were on the JV level), they were indeed competitive and finished the season with a 5-3 record. Flag High’s loss of talent was immediately apparent, as the Eagles finished 4-5-1, their first losing season since 1957, Ply’s first year at the helm; not only did half the city’s talent go to Coconino, but also half its high school population, which meant Flag High, now a school with roughly the same student body as Coconino, was still playing AAA ball against the Phoenix schools now twice its size. It’s a dilemma the Eagles had to face until realignment a few years later.

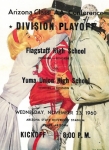

While Flag High was struggling, Coconino started in AA and played smaller schools closer to home. The Eagles’ 1968 schedule included South Mountain, Camelback, Washington, and Brophy, while the Panthers played Winslow, Globe, and Snowflake as they played their first year of completely varsity football. Because of scheduling commitments, Flag High and Coconino did not play each other.

The Eagles lost to South Mountain in the opener, 27-0, and it just got worse from there. Though several games in ’68 were more competitive, Flag High could not muster a single win, and taking the last game lost in ’67 into consideration, Ply’s Eagles had lost eleven straight. It was the first winless season in their long, proud history, but Ply didn’t give up, and he was prepared to stick it out and right the ship in ’69.

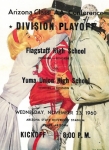

For as dismal a season as the Eagles had, the Panthers had the opposite in their rookie all-varsity campaign. They started the year with three wins in their first four games, including a key 6-0 win against Winslow, but a three-game losing slide threatened their season. They pulled out of the tailspin against Agua Fria, 13-7, and that started the flourish of miracles that ended the Panthers’ season. Against Agua Fria, David McNabb picked up a missed field goal attempt and raced 70 yards for a third-quarter touchdown that proved to be the deciding points; the win put them back in contention for the AA North title. The next week, at Paradise Valley, McNabb was Johnny-on-the-Spot again, this time picking off a pass deep in Trojan territory and running it in for a pick-six in the fourth quarter to give the Panthers not only the 13-6 win, but also the division title and, at 5-4, a berth in the championship game against Flowing Wells.

Against the Caballeros, the game ground down to a defensive struggle and a scoreless tie going into the final minute of play. Eleven turnovers were committed by both teams, seven passes total were completed, and the Panthers won the total yardage battle with a meager 129 yards versus Flowing Wells’ 118. With the Caballeros driving, in the red zone, and looking to score with mere seconds on the clock, the Panther D-line burst through and jarred the ball loose from the halfback’s hands; Rick Brenfleck picked it up on the bounce and rumbled 85 yards for the only score in the Panthers’ 6-0 win.

Against the Caballeros, the game ground down to a defensive struggle and a scoreless tie going into the final minute of play. Eleven turnovers were committed by both teams, seven passes total were completed, and the Panthers won the total yardage battle with a meager 129 yards versus Flowing Wells’ 118. With the Caballeros driving, in the red zone, and looking to score with mere seconds on the clock, the Panther D-line burst through and jarred the ball loose from the halfback’s hands; Rick Brenfleck picked it up on the bounce and rumbled 85 yards for the only score in the Panthers’ 6-0 win.

It was the first undisputed state football championship in the history of the city of Flagstaff.

Text for Flagcoco written by Russell Woods, original draft posted February 5, 2013

Last Updated: July 21, 2014

WORKS CITED

Arizona Daily Sun / Coconino Sun; Flagstaff, Arizona. Various editions from 1912 to 1968.

Arizona Interscholastic Association. Online. http://aiaonline.org.

Azcentral.com. “Spectacular Dugan’s story became bittersweet.” http://www.azcentral.com/sports/preps/articles/2007/08/09/20070809hof07dugan.html.

Fanbase.com. http://www.fanbase.com/Northern-Arizona-Lumberjacks-Football.

Kinlani. Flagstaff High School Yearbook. Various editions from 1923 to 1969.

Northern Arizona Yearly Results. College Football Data Warehouse. Online. http://www.cfbdatawarehouse.com/index.php.

Oberhardt, Robert. Eagles on the Mountain: Flagstaff High School Varsity Football 1923-2011, A Statistical History.

Prescott High School Sports Record Book, 1910-2007. Online. http://mypusd.prescottschools.com/pusdwp/phs/files/2011/04/athletics_sports_records_07.pdf.

Prescott Weekly Journal-Miner / Prescott Evening Courier. Various editions from 1915 to 1964.

Reflections. Coconino High School Yearbook. 1969.

Winslow Mail. Various editions from 1915 to 1919.

Going as far back as 1900, exhibition games have been played in

Going as far back as 1900, exhibition games have been played in  considerations, the influenza pandemic, and world war meant reductions in scheduling; they only played five games total in the three seasons from 1917 to 1919, four of them against Winslow.

considerations, the influenza pandemic, and world war meant reductions in scheduling; they only played five games total in the three seasons from 1917 to 1919, four of them against Winslow. A crowd of a thousand people (

A crowd of a thousand people ( of the third, Vic McClure ran up the gut to get the high schoolers on the board. The drop kick conversion failed, but the deficit was narrowed to 14-6. The ensuing kickoff was a squib kick, and Flag High recovered at midfield with growing momentum, but they couldn’t convert. They mustered one last drive, and hard running coupled with sloppy

The Championships of the 1930’s

Rollin Wheeler took over as the Eagles coach in 1929, and by 1931, they had their second championship, their first outright. They did it again in ’34 and ’35 under the field management of their first true superstar, Eddie Jakle; in the title-clinching game at Jerome in ’35, Jakle’s touchdown pass to David Turner proved to be the only score in the Eagles’ 7-0 victory. These two conference titles were considered state titles, even by the newspaper writers in Phoenix who believed the Eagles could defeat the powerhouse teams there and in Mesa. They even tried to talk up the idea of an extra game, a playoff, especially in ’35 between the Northern and Southern representatives to determine a true state champion.

Rollin Wheeler took over as the Eagles coach in 1929, and by 1931, they had their second championship, their first outright. They did it again in ’34 and ’35 under the field management of their first true superstar, Eddie Jakle; in the title-clinching game at Jerome in ’35, Jakle’s touchdown pass to David Turner proved to be the only score in the Eagles’ 7-0 victory. These two conference titles were considered state titles, even by the newspaper writers in Phoenix who believed the Eagles could defeat the powerhouse teams there and in Mesa. They even tried to talk up the idea of an extra game, a playoff, especially in ’35 between the Northern and Southern representatives to determine a true state champion.

ed only thirteen points in ’35.

ed only thirteen points in ’35. podunk team ever again.

podunk team ever again.

When a certain skinny freshman walked onto the Flag High field for summer practice in 1960, odds are neither Head Coach John Ply nor anyone else knew what they had on their hands. When he graduated in ’64, he was a chiseled hulk who had rewritten the record books, not just in football, but in baseball and basketball as well. James Dugan is not only the best athlete Flag High ever produced, or

When a certain skinny freshman walked onto the Flag High field for summer practice in 1960, odds are neither Head Coach John Ply nor anyone else knew what they had on their hands. When he graduated in ’64, he was a chiseled hulk who had rewritten the record books, not just in football, but in baseball and basketball as well. James Dugan is not only the best athlete Flag High ever produced, or For as great as his senior football season was, the basketball season started even better. If he was Jim Brown on the football field, he was Wilt Chamberlain on the hardwood, scoring points and grabbing rebounds like a man among boys. He scored 21 in the opener against

What is in dispute, even fifty years after the matter, is why the incident and the subsequent suspension happened. If you talk to Prescott people, they will tell you it was a tough, hard-fought game, as it usually the case when the Eagles and Badgers play in any sport, and Dugan couldn’t handle it, so he punched out a benchwarmer. Flagstaff folks will tell you Dugan was hacked and called racial slurs all game, the referees did absolutely nothing about it, and while no one condones violence, one could hardly blame Dugan for lashing out. For his part, Dugan considered the episode a moment of weakness, and he has always been apologetic about the matter.

For as talented an all-around athlete Dugan was, he never made it at

Against the Caballeros, the game ground down to a defensive struggle and a scoreless tie going into the final minute of play. Eleven turnovers were committed by both teams, seven passes total were completed, and the Panthers won the total yardage battle with a meager 129 yards versus Flowing Wells’ 118. With the Caballeros driving, in the red zone, and looking to score with mere seconds on the clock, the Panther D-line burst through and jarred the ball loose from the halfback’s hands; Rick Brenfleck picked it up on the bounce and rumbled 85 yards for the only score in the Panthers’ 6-0 win.